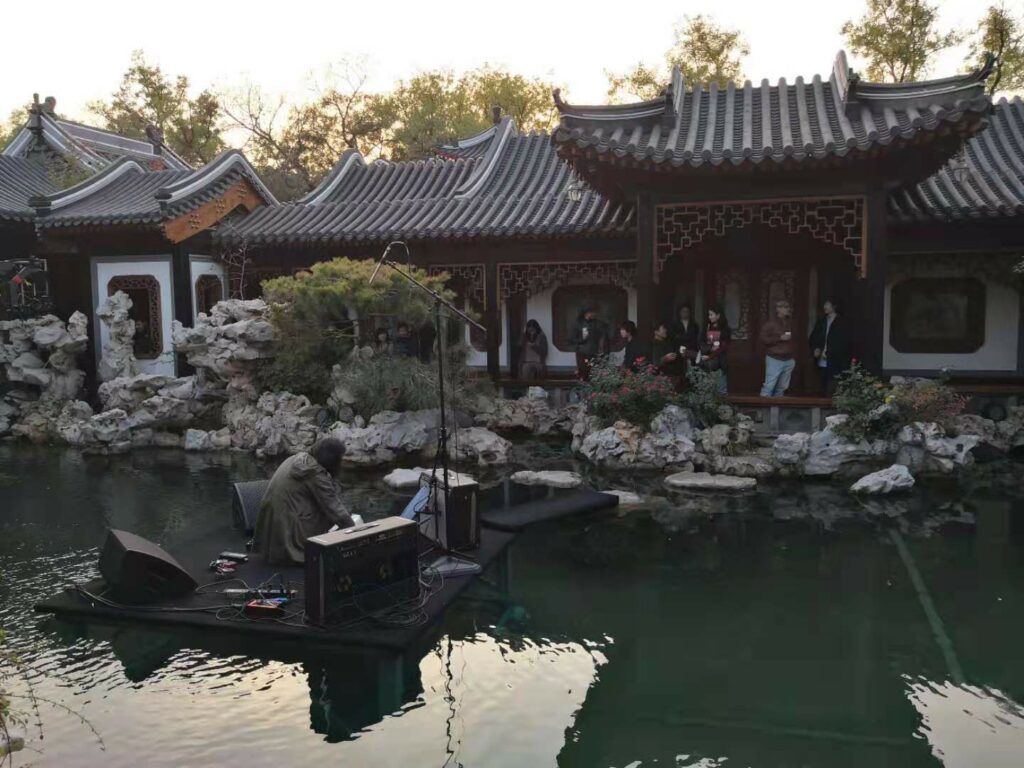

As a key figure in Beijing’s underground art/music scene traversing sound art, voice, electronics, movement and performance, there’s no better guide to the city’s subterranea than Yan Jun.

For his Counterflows At Home podcast Yan takes us on a journey through the place in which he has built his singular practice over the past 3 decades, winding together meditations on his own life and practice, interviews and music from artists in the underground music scenes, as well as insights into culture, history and politics today. A playful, funny and insightful voyage into a world little known outside its participants.

Scroll down for a gallery of accompanying image gallery of Yan’s Beijing, a DJ mix of key local music protagonists and an essay on the discourse around what constitutes music…’It’s OK if it’s Not’.

It’s Not Music

The artist Yan Jun guides us through the ‘non music’ scene in Beijing, starting from the four walls of his studio and travelling out to a busy underpass and a local restaurant to meet artists in the city to talk about what non music means to them. Yan noticed things starting to happen a few years ago, when a group of artists in the city began making performances which defied easy categorisation. These could take the form of one person having a conversation with their mum on the phone or an audience member disassembling a mandolin. In this podcast we hear Yan’s personal journey through the idea of non music as well as several artists and promoters who are at the centre of it, including Li Qing, the drummer in indie rock band Carsick cars, the promoter, musician and label boss Zhu Wenbo and outsider artist Ake, who taught herself violin after finding it in a local junk store.

The podcast was produced by: Alannah Chance

Artists featured in the podcast:

Zhu wenbo

Zhu wenbo is involved in many different music projects. He uses clarinet, saxophone, microphone, speaker, recorder, percussion and more, doing compositions, improvisations, events and publications focus on “music unlike music”.Li qing

Her official bio for miji concert is “a shonen” (a youngster). She is member of carsick cars, snapline, soviet pop and rat “the spy” 51. She is also an active member of Beijing based avant-garde music group “impro committee”.Ake

Born in Haikou, involved into words, sound, theatre and performing art.

The writer Kang He talked about his impression of Yan Yulong one day: loosey-goosey, half-dead.

Those may not have been his exact words, because my memory’s also loosey-goosey. But I do remember the show he was talking about. It was a “living room tour” in March, 2016. Kang He was part of the show. He was reading Jean-Pierre Jeunet in the bathroom. Yan Yulong was wearing an oversized coat, tattered old leather shoes, and a pair of wrinkly white gloves while playing the violin with a fuzzy bow that had a lot of dangling hairs. Of course, he never really touched the violin strings during that show, so the performance was almost silent. I say “almost” because the show wasn’t executed with precision. He accidentally touched the strings a few times. I don’t know if these “accidents” were intentional. Was it an imprecise musical style, or an imprecise personal style?

After writing this article, I checked the records. Yan wasn’t wearing gloves that day, and he wasn’t playing solo. So I must have mixed up two shows.

Kang He was born in the 1960s. His writing, including his “photographic writing,” is built on the foundation of many tiny units. They convert into and nest within each other. Though each unit is independent, the structure as a whole is grand, even repetitive. It conveys a strong sense of performance.

He needs performers to have an intense subjectivity, or at least make it not boring. He has an opposite: the still very much alive romantic culture, or the culture of agricultural civilization: continuous, symbolic, self-mythologizing. The subjectivity of this culture is also very strong, so there is a struggle, like Stravinsky and Nijinsky struggling with a Parisian audience in 1913. Is Yan Yulong another opposite of Kang He? I can’t say, because it’s obvious that Yan’s performative looseness is a tactic to avoid struggle, and the fighter might get angry because he can’t find his opponent.

According to traditional discourse, rock music is a struggle within a modernist structure that gives boys who are oppressed by patriarchal civilization the opportunity to cry, resist, and revel. Then what about the band Chui Wan, to which Yan Yulong belongs? And Snapline? They don’t seem to be partying, or maybe it’s better to say that they’re low-temperature. By the time the new band Kaoru Abe No Future appeared this year, it was almost a winter for bands in Beijing. Over the past 10 years, my main collaborators have come from this low-temperature background. From D-22 to XP, I’ve met some loose people. It’s hard to tell if they’re half-dead, but it seems that the overall libido is not strong.

OK, I don’t want to introduce a specific kind of music, let alone expose a specific scene. It’s better to say that I want to express some conjectures almost to myself, without objectivity or authority. This kind of conjecture means more to me personally than others, including those who talk about it and those who will read it. In other words, for other people, the meaning of these conjectures only exists as “Oh, this person thinks so.”

Let me introduce the idea: In 2014, I wrote an article titled “Absent of the Empire.” In it I wrote that melody used to be meaningful, but later lost its original function — that is, its direct relationship with people. In the 1990s, melody took on the function of comforting trauma, and at the same time it was invested in and mass-produced, becoming a melody of a melody, and a melody of a melody of a melody. We are like a stress-release device in the form of a song: all emotions have been preset, waiting to be stimulated, and then enter the cycle of reproduction. In this way, noise has its rationality, because it is not a metaphor, nor a symbol. It is not a set of symbols at all and cannot be converted into a set of meanings (like a dollar is converted into a few renminbi). The noise needs to be touched. So it appears outside the system and may rebuild direct contact with people.

I mentioned Adorno’s line, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” which means that poetry itself needs to be separated from the fictional symbol system. There can be no more romanticism, or romantic versions of classicism. Language must bear the responsibility, there’s no need to invent an ideal of Purity or Sublimity. After all, people are made of language. But because of my dislike of Adorno, I also said that Adorno’s words are inherently problematic. They’re arbitrary, absolutist, and handsomely expressed in a style that happens to be romanticism dressed as modernism.

Therefore, here is a conjecture about noise: I have a friend named Lao Yang. After reading Jacques Attali’s Noise: The Political Economy of Music ten years ago, he said that noise is resistance. At that time, we all liked loud noise, psychedelic noise, and strong and loud improvisational music, “Life is unrestrained.” But I was also studying other noise: calm noise, quiet noise, randomly loud randomly silent improvisational music. I guess noise does not mean resistance, because if noise is free, then it has no meaning. If it is meaningless, how can it be converted into the meaning of “resistance”? However, having said that, if this kind of noise is like a murmur in daily life, and is completely meaningless, then what should we do? What is the difference between this work and that work, this noise and that noise? So this conjecture continued for the next ten years.

In 2009, Zhu Wenbo began to organize concerts at D-22 every Tuesday, a weekly series called “Zoomin’ Night.” Anyone could try something, even if they didn’t know what it was. In other words, they could openly experiment, but it was not necessarily experimental music. Later, some of the people who went there often came up with the term “cold band”, or “cold music”. That is, an opening band that’s supposed to warm the audience up, but the result is off, and everyone feels awkward. [Translator’s note: the Chinese term “冷场” literally “warm field,” is used for opening bands; the term “冷场” is an inversion of this, swapping “warm” for “cold”.] I really like this kind of cold joke. When I’m embarrassed, or when others are embarrassed, I experience strange electric currents, as if I had lived an extra day. Well, the name “Zoomin’ Night” is an allusion to P.K.14. P.K.14 is also not very hot, a little twitchy, but it’s still difficult for everyone to understand why it became cold. My guess is that this group of people is really not talkative. This may have something to do with personality, and it is also in line with a certain social ethos. They don’t talk, show off, or have children.

I guess society is oppressive to language. On one hand, there are too many new concepts, information overload, people don’t have language sufficient to understand and describe the world. Incoherently written slogans proliferate, which leads to the return of the old language. This can also explain why melody is so popular today. On the other hand, the crushing of society is not necessarily carried out at the economic and political level, but at the linguistic level first. For example, as the existence of verse and repetitive phrases, whether they’re official slogans, workplace exercises, or additions to children’s Confucian textbooks. These reflexive rhythmic cycles are first of all a technique for managing the body, and also a means to suppress an individual’s language production, sending people back to the ancient collective pre-linguistic state. This also explains why the rhythm in music today is relatively simple. You might say that dancing in the public square is a half-dead existence, but in the final analysis, who is willing and able to live completely?

There are also hot words on the internet. These include special languages from all kinds of scenes and subcultures, such as the particularly reasonable mode of speaking used by stock critics. People use it to come to terms with the disorganized, incoherent state of things. We therefore have a sense of shared identity and belonging, and we can also exclude some people. Each word corresponds to a specific reaction, and within each reaction is a community. It’s just like before when people watched TV, they watched the same programs, learned the same words and cultural references. This is practically enough to birth a nation. However, in the background, it’s precisely the opposite trend: people are becoming more and more disorganized and incoherent, they can’t understand what the other is saying, and very few people are willing to speak in a native, personal language. It’s like a supermarket full of goods. Choose which country to be in like you choose which product to buy. People who sew their own clothes have no nationality.

Zoomin’ Night ran until 2015, when XP closed. There are many people in the “cold music” field. I am familiar with: Zhu Wenbo himself, Zhao Cong, programmer Li Song (now in London), Li Qing and Li Weisi (and their duo “Soviet Pop”), Yan Yulong, Liu Xinyu (who’s now concentrating on being in a band). In 2014, my previously irregular “miji concerts” began to be regularly scheduled at Meridian Space (until the end of 2017), and they all participated often. Some of these people with whom I’ve collaborated fairly frequently can play an instrument, including electronic equipment, and some can’t. Most of them are also members of (low-temperature) rock bands. The meaning of miji is actually to streamline, to purify, because in the past I’ve already booked too many shows, talked too much. They will remind me to talk less.

Then one time, around 2015, I put together a living room tour with a few of them and met Ake. She was a spectator, and cooked in exchange for entry to the performance, but the sound of her (and illustrator Shu) cooking also counts as part of the show. Later, she got a violin from a waste recycling station, and then began to perform. She also doesn’t like talking.

Because she has no musical experience at all, she can only perform things that are nothing, like a constant but not very stable bowing: guuuuhhhh —— zzzhhhiiiiii. Later, she added more and more elements of performance art and body art. Later, more and more compositions appeared around her, and she also composed. That is to say, compositions closer to the early Fluxus idea of a command-based composition, but a little longer, and usually not shocking.

So at the same time, Zhu Wenbo’s compositions may be based on simple foundational logic; Yan Yulong’s on classical minimalism (now he, Sheng Jie and Shouwang are working on a composition-focused label called Maybe Noise); my own compositions may lean toward being more conceptual or performative. The topic of composition has been very common in improvisation circles around the world for the last ten years, maybe because it helps to impair an excess of “ego” in improvised music, or maybe it’s just a desire to seriously play small games. Of course, others may think that this cannot be considered composition, and so just call it “instruction.” In short, they are all unrestricted, super simple works requiring no skill. In terms of effect, they are usually quiet, but do not create an atmosphere — they mix into the environment.

Ake’s existence provides me with another conjecture, that is, an extension of the purification concept that I mentioned before: If the tension is removed, does an intense silence transform into something less intense? This brings up a question about “quiet” post-Cage: quiet has been objectified, it’s already become very loud, and it is not open. In other words, it was originally a non-verbal state, but now it’s a language, and a dead language. Buddhist allegory turned into a dead machine. Ake’s loosey-goosey works made me think about whether it’s possible to bring quiet back to “silent.” Just silence and nothing more. This way, not only does noise’s intense meaninglessness change into “meaninglessness and nothing more,” but also self-expression is quieted from the source.

After Ake, there was another person who had no musical experience named An Zi who also turned from an audience member into a performer. She was also very quiet. Her first performance was to burn potato chips one at a time. One of our recent collaborations involved each of us recording fragments from “King Lear” on our mobile phones, and using the recordings to improvise a dialogue. Her quiet can convey weird things, and it is not relaxed at all, sometimes even makes you feel nervous. My theory here is that the purification process is to remove impurities, to go from “silent” to “quiet.” It’s also removing impurities to go from a live performance to a recording studio, even more so. How can we purify the impurities themselves then? Do impurities need to be purified?

Soviet Pop also brought me a conjecture. It’s mainly about Li Weisi playing a four-track tape machine. His sound is ambiguous and slow, making it hard to know what’s deliberate, what’s machine noise and what’s manipulated. There is also no so-called structural logic. This is different from the language of modernism as a whole: it refuses to be analyzed. In this kind of performance, man and machine are one, music and daily life are one, useful and useless are also one. Later, at a miji concert in 2018, Li Qing performed a work called “A Thing [I] Want to Do” I don’t want to describe it, I just want to say that this simple “want to do” makes all of these other things bear fruit; it’s initiative. Language does not have to generate a stable form. It only needs to provide the possibility of “generation”. This is the initiative of the author, and it encourages the initiative of the audience.

In 2017, Zhu Wenbo and I co-curated a cassette called “there is no music from china”. This was done at the invitation of a label from New Zealand. I guess they wanted to announce a “music from China”, so we played with this expectation. But at the same time it could also be “something from China called no music”. A pun game. From this perspective, gaming seems to be a more important layer than embodied reality: brain teasers, not passion, cadence, or the expression of attitude.

But if games are also a part of embodied reality, it may be easier to understand: I guess that the body is also crushed by reality. For example, many people are clinically depressed, and some have already died. This isn’t normal. The body may respond with a language structure different from that of an asphalt roller. For example, it may not be interested in verse, it may not be interested in turning into another behemoth, or it may use the language of neurosis or depression, or it may be unable to speak, may only be capable of trembling and whispering. In short, it does not necessarily produce meaning, but it will face the reality of excess meaning, a reality where meaning circulates within itself. Those loosey-goosey bodies are also bodies, and they form their own logic (maybe it should be considered weak logic?). If the body can be regarded as a kind of machine, and bioelectric phenomena constitute the illusion that we call “self”, then, whether or not it’s a game, a hum, or a logical short-circuit, this machine is doing it with the power of the self. It does this often, it couldn’t be more natural.

When I say this, I am not trying to create an elevated sense of what me or my friends are doing. Moreover, these aren’t things that happen as a result of discussion. It’s just conjecture, nothing more. It’s ok if these observations are all wrong, it doesn’t matter.

Yes, around 2017 or 2018, Zhu Wenbo changed his profile to: “dedicated to music that is not like music”. In 2018, I started writing a series of essays called “Maybe Not Music”. Then, also in 2018, we started a series of performances at the Goethe-Institut, mainly in collaboration with German artists, called “Not a Concert”. That included sound and light installations, contemporary dance, performance pieces similar to theater, European Reductionism, group performances in which everyone goes in their own direction…… After the second performance, a German friend talked about our (“Improv Committee”) work. She said that some people’s sounds were too loud, drowning out the sounds of others. My personal understanding is this: balance and democracy are European traditions, but if I believe in equality between sounds, then I should believe in equality between loud and quiet, and create opportunities to showcase this equality. Of course, reality does not necessarily match this interpretation, and it doesn’t need to, but people’s understanding of things will definitely influence how they act.

In short, there are a lot of things referred to as “experimental music”, “avant-garde music”, and “sound art”. I’d rather what I talked about above not exist in these categories. It’s true, because discourse transcends reality, it conveys a direction, not a fact. This music, or whatever you call it, is just fact, nothing more. These things are not of any importance, they’re only relevant to a small handful of creators and an audience of 10 to 100 people. Maybe they’re not worthy of being called music or art. Fortunately, they do not waste societal resources, and they make these people happy. So it doesn’t matter if it’s not music. That’s it.

Outliers

A radio/DJ mix by Yan Jun. My (Non) Music Enlightenmentt